The Youth In The City: How The Youth Have Experienced the Decline of Trenton.

The date was April 9th, 1968, just under a week from Martin Luther King Jr’s death. Riots are popping off all over major cities in the United States, tensions rise to a level never seen before, and Trenton is on fire.

The streets were filled with anger and crowds galore, most of them being young black men. Thick smoke arose from the buildings that had been vandalized, items were strewn across the streets, a once united city was in chaos. The riots, sparked by MLK’s death, as well as other issues at the time, caused the youth to become active in a major, and violent way.

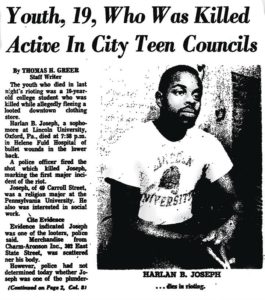

Then, a gunshot, and a body falls to the ground, dead as a door-nail.

The next morning, the sun rises on a new Trenton. The youth had just exercised the most vulgar display of demonstrating in the city’s history. However, in that display, they lost a voice of reasoning and peace.

Harlan Joseph, a 19-year-old activist in councils among the city, had been shot and killed in the midst of the chaos. According to the article, He had thought to have been a looter by police, and then was suddenly gunned down. It seemed that the riots had caused this, and it was all pinned on the reaction to the death of MLK.

However, there is more to the story than just the death of MLK, or the death of Malcolm X. It all started with the systematic tear-down of segregation, and then it started a chain reaction that lead to the youth uprising.

Part I: Before 1968

Before the dawn of the 1940s, Trenton was a very affluent capital of New Jersey with a bustling landscape of all races and classes. It was a place where any person of race, class or gender could work and thrive in a bustling community.

While it may not be shown if one were to walk around, Trenton’s Historical Society preserves the remnants of what was once a thriving city. IN fact, Trenton’s Black community was affluent, despite the troubles and obstacles at the time.

One of the most notable African-American organizations was the YWCA Montgomery Branch on Montgomery Street. The YWCA is an organization that focuses on eliminating systematic racism and creating equal opportunity for the disadvantaged.

Established in 1927, according to the Historical Society, the organization garnered over 170 members in the opening year. The building also housed special events for African-Americans to meet each other and just have a nice night out engaging with one anther in various activities.

Another major building was the Eclectic Club on North Broad Street, which housed speakers dating all the way back into the late 1800s. These speakers would talk to a predominantly black audience and would be a social club for non-speaker events, in which the community would socialize with one another and get to know each other better.

IN 1888, Frederick Douglass spoke there, and it was a social spot for the “Black Elite”, or those form the south who were able to purchase property and remain free men.

There were many other churches, schools and organizations in Trenton during this period that were listed in the Historical Society as significant to the African-American culture.

In Albert Stark’s “The Statement”, the book describes the Jewish neighborhoods of Trenton being very prosperous and very lively, co-existing with other neighborhoods filled with Blacks, Christians and other neighborhoods.

Stark stated in an interview with NJ Jewish News in 2016, ““We walked everywhere. I went to Junior 3. It was great growing up in Trenton. We had a neighborhood that was predominantly Jewish but was very mixed. We were the middle-class kids; the rich kids lived in Hiltonia, the downtown kids on Market and Lambert streets.”

However, despite the ability to own property and live freely as best as they could, there were still problems with segregation.

In historian Jack Washington’s “The Quest for Equality”, the book details the Black community’s struggle to overmount the problems with segregation in Trenton. The book describes how Trenton residents in the community could not enter specific places or do anything similar to their white counterparts without obstruction from loopholes in the laws and sentiment.

One of these issues led to a case that turned the course of history.

In 1939, two black families, knows as the Hedgepeth and Willams families, resided in Trenton. Both families were of African-American dissent. When trying to enroll their children into the public school system, they were told that their children were not allowed to attend public middle school on the basis of their race. Their mothers attempted to appeal to the principal, superintendent and the board in order to give their children the best education possible. All three turned the away.

Five years later in 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that the children were unlawfully discriminated against, and the district was rquired to integrate desegregation into all of their schools. The case also outlawed denying admission based on race or skin color, setting the precedent for the now widely celebrated and landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

The children, now able to go to schools that they wished to, now had the same opportunities as their counterparts. With that, many began to join councils, get a better education, and actually voice their own opinions.

Part II: The Civil Rights Era

While Trenton continued to bustle, there was some tension in the air. Despite the progress being made against systematic Jim Crow laws in Trenton, the people did not feel that it was enough to curb police brutality, segregation, and other inequalities.

In an article online from Chris Baud of the Trentonian, archived by CapitalCentury, the first known demonstration took place on October 26th, 1963, in which 4,000 to 10,000 marches, most of them young and of minority status, took a mile-long journey through the streets to protest injustice and systematic racism.

Led by Reverend S. Howard Woodson, the march was focused on the economic, social fronts of Trenton, as well as the well-being of the citizens of Trenton. Most of the participants were high school students, college students and young adults who knew that they refused to continue to live in a life of segregation. They were joined by white counterparts in solidaryity to progress though this time.

The writer also interviewed Catherine Graham, who was head of the Trenton NAACP, about the era.

“Young Kids don’t realize what it was like. They get offended by something that’s nothing. They don’t know what it’s like not to be able to go certain places or do certain things. If they wanted to do something, they can do it.” Graham told Baud.

Shortly thereafter, Trenton became a very active place for black-rights groups and organizations, in which there were meetings almost every week featuring speakers from Coretta Scott King to followers of Malcolm X.

However, building tensions erupted one night in April…

On the night of April 9th, 1968, five days after MLK’s assassination, Trenton experienced the worst acts of violence, vandalism and rioting it had ever known to experience. Charles Webster documented it as “The riots that killed Trenton.” It was the riots that set the road for the Trenton we are presented with today.

According to archives from CapitalCentury, there were more than 200 businesses that were broken into, looted and left in a state of disrepair. 300 rioters, all of different ages and races, were arrested on various charges ranging from assault to robbery to arson.

The worst was that the city was out $7 Million at the end of the rioting, and lost insurance as companies withdrew from the city in droves, thwarting any rebuilding efforts. This now set the precedent for Trenton’s future: A city without money.

However, Trenton’s riots may have had also been inspired by other uprisings in the state a year prior. Lawrence Hamm, Chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress, remembered the Newark uprising, sparked by numerous events.

“The first real Civil Rights protest in Newark took place at a White Castle,” Hamm said in a small presentation to a Class at The College of New Jersey in April, “Black people could eat there but they couldn’t work there.”

Hamm then began to describe the event in which two Newark officers violently beat and then arrested a black Taxi cab driver, John Smith, for simply passing a double-parked car. He was then beaten savagely, arrested, and charged with false crimes.

From there, the next day, a protest was organized, which quickly spiraled into an all out riot, where businesses were firebombed and looted. The riots spread throughout the city so violently, that the National Guard was brought in.

“I watched the military roll up my street that night…16th avenue…and I didn’t know this was going to happen, but other people knew,” Hamm said. “Jersey City had an uprising the year before…most cities in New jersey did in the 60s, and it really didn’t end until Camden had its uprising in 1971.

What made it worse, was the media’s portrayal of the riots. The Kerner Report released by Congress just two months before the riots, warned about the Media’s portrayal of the Civil Rights movement, stating that it was an incendiary factor in the race riots of 1967, potentially as well as the subsequent riot in Trenton.

“The Communications Media, Ironically, Have Failed to Communicate.” The report said.

The media, according to the report had failed to adequately report on arrests, damage, contributing factors and instances of excessive force used by police and the national guard, virtually over-sensationalizing these incidents. The media also used slang terms to describe the black communities of America, making them ticking time-bombs over the racism not just on the street, but in papers and television in front of a national audience.

Part III: After The Riots (Post-1968)

Since those riots, Trenton has never recovered to the bustling epicenter it once was for commerce and prosperity. Wealth has vanished, the youth have become susceptible to violence and drugs and Business has vanished.

As of today, Trenton saw 162 shooting incidents in 2016, a 40 percent increase between 2015 and that year. Overall crime in the capital rose by 2.3 percent, especially homicides. Robberies were still at all time highs, and overall crime was still at near-record highs.

The US census bureau showed the city of Trenton still behind in labor force participation rates, Poverty still remained over 25 percent, Household income remained stagnant in 2016 at under $35,000, and business establishments still remained scarce in the capital city.

However, the children are being impacted the most, especially in their educational means. According to TownCharts.com, an education monitoring site, showed that barely 75% of residents have, at least, a high school education and less than 15% have a bachelor’s degree. Dropouts were alos higher than the state average, clocking in at nearly 30 percent.

IN some cases, poorly funded schools in Black communities seem to struggle without funds, while affluent areas that are predominantly white perform the best and get bonuses.

Drugs also remain a problem in Trenton since the 1980s crack epidemic, in which a severe influx of crack cocaine infiltrated the most vulnerable parts of the city, predominantly the poor areas that were mostly black, and filled the streets. These caused massive drug rings to spring into the limelight, in which students were paying money for Crack-Cocaine, or even using stolen goods as a form of payment.

The youth are struggling in Trenton, despite the successes of the civil rights movement, as well as its long-lasting legacy in inner cities. Despite the city’s best efforts to try and fix the problems plaguing the youth and the city, the scars of the Civil rights movement and the riots still remain.

However, there is still a feeling in the city that the city will return to what it once was. However long that will be still remains to be seen.

Whether it’s optimism, spirit, pride, or the ghost of Harlan Joseph looking down on the city giving the blessings he can, there is optimism though the darkness. For every broken block, the youth can discover a silver lining to follow, and build upon.

Sources:

Alperin, Michele. “Exploring Trenton’s ‘Jewtown’.” NJJN, New Jersey Jewish News.

Baud, Chris. “1963: Marching for Civil Rights.” CapitalCentury, The Trentonian/ Trentoniana.

Mickle, Paul. “1968: The Trenton Riot.” CapitalCentury, The Trentonian/ Trentoniana.

Mickle, Paul. “1985: The Crack Scourge.” Captial Century, The Trentonain / Trentoniana.

Shea, Kevin. “Crime Was up in Trenton Last Year, Led by 40 Percent Jump in Shootings.” NJ.com, NJ.com / AdvanceLocal.

Stark, Albert. The Statement. Outskirtspress, 2016

TownCharts. “Trenton NJ Education Data.” Towncharts – Trenton, NJ Education Data, Towncharts.com

Trenton Historical Society “List of Historical Sites in Trenton. (19th / 20th Century)”

“U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Trenton City, New Jersey.” U.S. Census – Trenton, NJ QuickFacts, U.S. Census Bureau.

Washington, Jack “The Quest for Equality: Trenton’s Black Community, 1800-1965”,

Mr. Lawrence Hamm for his Wonderful Interview.