The Remediation of Brownfields into Community Spaces

When a town is planning the construction of a new library building, they do not typically have to contend with the possibility that hazardous pollution from the nineteenth century is lingering in the soil. Regardless, that was the situation the Princeton Borough Council and the Princeton Township Committee found themselves in as they jointly embarked on their public library’s expansion, and the process would ultimately involve the removal of thousands of cubic yards of contaminated soil from the property.

“They were testing groundwater. They were testing the dirt. They were testing everything to make sure there was nothing left on the site that was dangerous,” said Leslie Burger, who was the executive director of the library at the time of the remediation project.

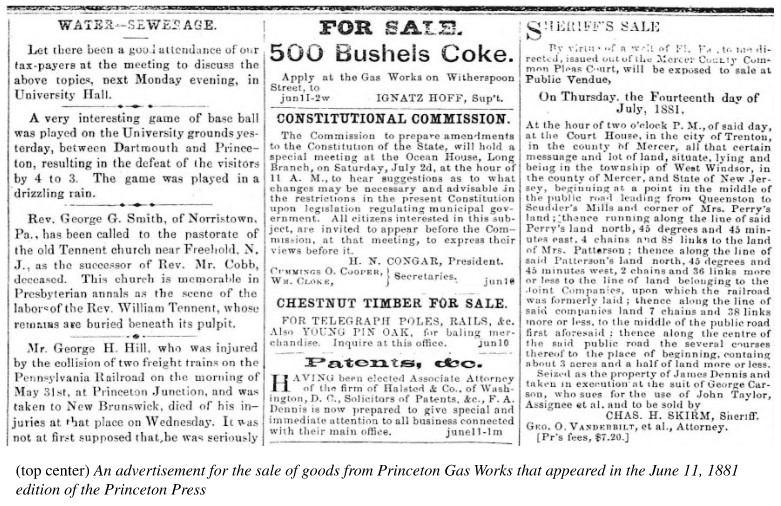

The Princeton Public Library rests on property that once belonged to the Princeton Gas Light Company, a business which formed in the mid-nineteenth century. The company’s site on Witherspoon Street was home to Princeton Gas Works, a coal gasification facility which operated there from the mid-1850s until 1911. The property was purchased by Princeton Borough over four decades later, in 1958, and local papers reported on the opening of a public library on the site in 1965.

It would not be until the 1980s, long after the public library was built, that the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) flagged the property as a potential brownfield, or piece of land whose use is complicated by the possible presence of pollutants released by industrial activity on the site.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that there are more than 450,000 properties classified as brownfields in the United States. Lingering pollutants found in these locations can be hazards for the health of the surrounding communities and ecosystems, though the level of danger posed by a brownfield varies depending on the types of contaminants present and their concentration in the surrounding soil, water, and air.

An analysis conducted by the EPA that looked at data collected between 2015 and 2019 found that the populations within three miles of the 27,030 brownfield sites surveyed contained higher percentages of minority residents, low income residents, linguistically isolated residents, and residents with less than a high school education than the overall US population. The report does note that the hazard of living in close proximity to a brownfield can vary depending on each individual site’s history and type of potential contamination.

The proximity of brownfields to minorities noted by the EPA is present in the specific case of the Princeton Gas Works site, as its location on Witherspoon Street is just a block or two away from the Witherspoon-Jackson Historic District, which was where Princeton’s African-American community was restricted to residing under segregation.

Some of the earliest recorded concerns Princeton residents had about the grounds of their library were expressed in local papers in the 1980s. Residents were worried about the possible presence of carcinogens associated with gas manufacturing plants in the site’s soil after the NJDEP flagged the site as a potential brownfield based on its coal gasification history.

Yina Moore, a lifelong Princeton resident, was on the Borough of Princeton’s planning board during the construction of the new library and the site remediation process. She would go on to serve as mayor of the borough several years later, beginning her term in 2011. Moore does not recall there ever being too much concern in town about potential contaminants at the site.

“The whole movement was more so to modernize the library space, which understandably would result in whatever cleanup was necessary knowing the site history,” Moore said.

Later reporting by Town Topics indicated that the site was not a top priority for the NJDEP because of the five-inch concrete cap covering much of the property that prevented direct contact with the potentially contaminated soil. Consequently, plans for a preliminary site investigation were not mapped out until 1998, when Princeton was interested in constructing a new, expanded library building, a process which would involve removing the asphalt capping the brownfield.

“The impetus for the project wasn’t concern about the safety of the site for nearby businesses and their owners and customers and that’s very interesting,” Moore said. “ especially if similar sites elsewhere are located near more residential areas.”

The plans for the 1998 investigation are publically available under the title “Former Princeton Gas Works Site, Preliminary Assessment and Site Investigation; Prepared for Public Service Electric and Gas Company” in the Princeton Public Library.

These site investigation plans featured a number of measures meant to determine if the property was a danger to the community, including drilling to test both the soil and groundwater at the site. But plans to determine the safety of the property didn’t stop below the ground. They also included air quality tests, which were set to be conducted before work began, throughout the soil remediation and construction phases, and after the dust from construction had settled.

Several local papers reported on the results of the investigation, indicating that the carcinogen coal tar was the primary pollutant found in the soil. A Town Topics article from July 3, 2002 reported that in the end, Princeton hired Creamer Environmental to cart away 40,000 tons of soil from the site and replenish the area with clean soil.

“We were very careful every step of the way to be as transparent as possible about informing people what we were doing, what the borough was doing and how the soil was being removed,” said Burger.

She said she and others involved in the project maintained this transparent communication by speaking at town meetings and regularly communicating with the local press.

Work on the site investigation plans began in 1998, and the new Princeton Public Library building opened its doors in 2004.

When she was hired as executive director of the library in 1999, Burger wanted to take the opportunity to instill the expanded public library building with more life and vibrancy than it previously had.

“My idea was that the library could become the community’s living room,” said Burger. “That it could be the center of civic life in downtown Princeton.”

From the site of the former Princeton Gas Works came a bustling community center. The story of the site’s journey to remediation can serve as an interesting case study when considering the prospect of remediating brownfields elsewhere.