Facing Segregation in Mercer County Schools

Rachael Cenicola, Maeve Franklin, Katelyn Nieuzytek, Ciana Roman

How Did We Get Here?

by Maeve Franklin

Considerable efforts have been made since the 1800’s in order to force the school board to integrate the schools in Trenton. In 1879 Priscilla Herbert graduated from the New Jersey State Normal School(TCNJ) and was the first African American to do so. Her brother, Robert Henri Herbert would be instrumental in challenging the state on the issues of segregation(McGreevey). In the same year that Priscilla would graduate, a black couple would request that their child attend the all-white Market Street School in Trenton(McGreevey). They were denied by the superintendent Dr. Shephard. Henri Herbert brought the matter to the State House. Accompanied by other black families, he lobbied for a new law to be passed to desegregate the school district.In 1881 New Jersey passed a bill that states that no child between the ages of five and eighteen could be excluded from a public school based on religion, nationality or color. Unfortunately the 1881 law was not enough to solve the segregation issue.

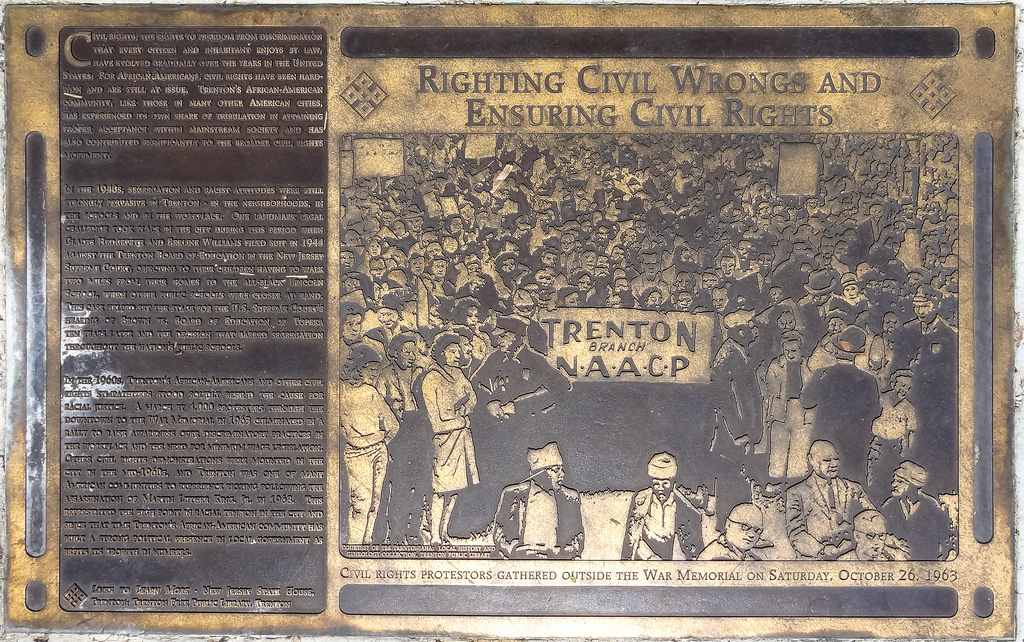

In 1932 the Trenton Central High School was opened and even though the school admitted both black and white students they were not afforded the same privileges. Black students were not allowed to attend swim classes with their white peers. The black community filled a suit with Robert Queen as the lead attorney(Washington). The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that the school had to provide equal access to all of its facilities. This would not be the last time that Robert Queen would challenge the Trenton School System as in 1944 he would become the lead prosecutor in Hedgepeth Williams v. Board of Education. Both Gladys Hedgepeth and Berline Williams worked as volunteers for the NAACP and were well equipped to deal with the publicity that the case would bring. Despite the fact that their children had attended elementary school with their white peers, they were being forced to The New Lincoln School. The New Lincoln School was the designated middle school for black children. Berline Williams and Gladys Hedgepeth decided to fight for their children’s right to join their friend in middle school(Washington). The 1881 law that was fought for so many years before was instrumental in the case being ruled in Hedgepeth and Williams behavior. 10 years later the case was used by Thurgood Marshall as one of the precedents for Brown V Board of education.

Despite the accomplishments in the courts, de facto segregation was still prominent perhaps most exemplified in superintendent Paul Loser’s reluctance to integrate the middle schools. Prior to the case rulings, Mrs. Williams and Mrs.Hedgepeth requested that their children be allowed to attend Junior No. 2 with their white friends, citing distance,unequal course offerings and unequal facilities as their reasons(Wells). Loser prevented their request from being fulfilled. When questioned during court proceedings he showed unwavering support for the current segregationist policies despite being aware of that it was technically prohibited by law (Wells). Loser believed that black children couldn’t be accepted by their peers or develop through their teen years normally in integrated schools. Without the pressure from Black and Jewish parents in the Trenton Community for Unity who wrote letters and gathered professional support for the integration of the school, of whom Roscoe West was a strong supporter (Wells). Combating the Jim Crow era laws was just the first step in ensuring their children were able to graduate with the necessary skills to attain higher paying jobs as the black schools them to become laborers rather than businessmen (Wells).

Although the desegregation of the schools was a major accomplishment, the integrated nature of the schools was unfortunately short lived as flight from the neighborhoods and redlining contributed to the segregation we see today (McGreevey). As the middle class families moved into the surrounding suburbs those who were left were poor people of color who could not afford to move out. Many Black families faced obstacles when moving out of these neighborhoods as they were intimidated, ostracized and denied mortgages and loans when they attempted moved into white suburbs. Realtors also did not show black families house within these neighborhoods thus ensuring black people had to stay within the poorer parts of the city(Reid). Black realtors were also prevented from joining the Mercer County Board of Realtors(Reid). This is part of the reason for income disparities seen in Trenton today (Reid). Another factor was the redlining in Trenton. Only certain neighborhoods such as the North Ward of Trenton were available to black families and the banks would only give mortgages to black families buying in red zones(McGreevey).When Black families did manage to move, the white families would often panic, sell their houses and move away. Housing discrimination is a large part of the patterns of segregation and the disparities in the qualities of segregated schools. In New Jersey the school district you attend is usually within the boundaries of segregated municipalities. Therefore because New Jersey’s housing is still segregated due to the effects discrimination had on wealth attainment for people of color, the schools are too(Latino Action Network et al. v. New Jersey State Board of Ed.). Despite the fact that segregation based on housing discrimination was found to harm student Booker v Board of Education, City of Plainfield, little has been done to remedy the issue. New Jersey has more than 600 school districts and because of this the interdistrict segregation is easily maintained. When one observes Trenton history, it becomes apparent how institutionalized racism is harmed the quality of its education.

New Jersey simply must do better. The segregation of its school system is actively lowering the educational attainment of its minority students. Low income Black and Latino students who attended socioeconomically diverse schools are more likely to graduate from both highschool and college(Latino Action Network et al. v. New Jersey State Board of Ed.). Allowing students to attend schools outside of their district or consolidating districts could help to integrate the school system and ensure a more equitable system for everyone. As Professor McGreevey said in our interview “People don't necessarily know how to understand each other's histories because they live in segregated spaces”. New Jersey’s students are being done a disservice by not being adequately prepared to function in integrated spaces. Once they do reach more integrated spaces like TCNJ, without having previous experiences outside of their own racial and socioeconomic groups, it can lead to the microaggressions and outright racism that is sometimes seen on college campuses. If New Jersey truly care about the future of it's you then enact policies that ensure an equitable education for all of its students.

Reid, Conner. "Thoughtless Action" and "Unwritten Law": Methods of and Response to Housing Discrimination and Intimidation in Trenton, 1950-1959. 20 Dec. 2016.

Franklin, Maeve, and Robert McGreevey. “History of School Segregation: Interview with Prof. McGreevey.” 5 Dec. 2018.

Washington, Jack. The Quest for Equality: Trenton's Black Community, 1890-1965. Africa World Press, 1993.

Wells, Lauren. “Thesis with Janie Butler Interview.” The College of New Jersey, 2012, pp. 1–72.

SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY LAW DIVISION: MERCER COUNTY . LATINO ACTION NETWORK; NAACP NEW JERSEY STATE CONFERENCE; LATINO COALITION; URBAN LEAGUE OF ESSEX COUNTY; THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH OF GREATER NEW JERSEY; MACKENZIE WICKS, a Minor, by Her Guardian Ad Litem, COURTNEY WICKS; MAISON ANTIONE TYREL TORRES, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, JENNIFER TORRES; MALI AYALA RUEL-FEDEE, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, RACHEL RUEL; RANAYA ALSTON, a Minor, by Her Guardian Ad Litem, YVETTE ALSTON-JOHNSON; RAYAHN ALSTON, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, YVETTE ALSTON-JOHNSON; ALAYSA POWELL, a Minor, by Her Guardian Ad Litem, RASHEEDA ALSTON; DASHAWN SIMMS, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, ANDREA HAYES; DANIEL R. LORENZ, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, MARIA LORENZ; MICHAEL WEILL-WHITEN, a Minor, by His Guardian Ad Litem, ELIZABETH WEILL-GREENBERG Plaintiffs, v. THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY; NEW JERSEY STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION; and LAMONT REPOLLET, Acting Commissioner, State Department of Education, Defendants. . 17 May 2018.

Getting the Quality Education Students Deserve

by Ciana Roman

From the beginning of life, all humans are unique and like no other, and yet they are all equal in worth. All people, despite their backgrounds, are entitled to the opportunity to work in order to better and maintain their life. Although Americans pride themselves in their founding morals, the opportunities in this country are not truly equal for all citizens. Governmental segregation of cities and regions occurred at the beginning of the 20th century, forcing the progression towards equality into a slow, almost stand-still crawl. In Imani Perry’s excerpt “Reading, Writing, and Rights” from Quality Education As a Constitutional Right, she writes, “African Americans were systematically excluded from purchasing property in what were or would become affluent areas (and good school districts)”. By being excluded from these affluent areas and the quality education provided in them, African Americans were put at a great disadvantage and not given the tools to better the situation. The funding of these schools is based on the financial status of the district, providing poor education in these areas and furthering the advantage gap.

Education funding is always a debate struggled with in America. Dr. Colette Gosselin, a department chair for TCNJ’s School of Education, gives her insight on the dilemma: “We need to provide all schools with funding to meet the needs of their students.” She explains that schools in poorer communities need more funding and better-qualified teachers, which can make all the difference in a student’s education. She shows that funding can provide more experiences, resources, and opportunities for disadvantaged students. When asked about the taxation of the people for equal education despite financial and racial status, she responds with the fact that we should care for society as a whole, even economically. Gosselin remarks, “When we address the needs of all members of our society, economically we actually do better in our country.”

One of the problems faced when attempting to provide funding for education is the resistance given by the wealthy when it comes to taxation. This resistance is not without reason, from the perspective of someone who either they themselves or their parents worked for their fortune it can appear as though the government is punishing them for attaining money. While this is a fair perspective it fails to take into account that whether through monetary means or simply the cognitive ability they were born with, every individual has advantages and disadvantages that allow them to succeed or not in life. Whether or not a person’s fortune is attained through genuine hard work, there are some people that are not provided with the tools necessary to achieve the same levels of success. Taxation for education funding is one of the most necessary taxes because education is what provides people with the ability to better their lives and provide their family with the means for survival. “Republicans believe strongly in an educational system that will provide higher education to those whose achievements deserve it” from Republicanviews.org, this is a quote that leads to implications when considering students backgrounds and the box that can restrict their growth. Some students are living in conditions that do not allow for a satisfactory performance in school, to limit students based off of their performance in high school, the education of students must be as fair as possible being provided to all districts equally. It's hypocritical to claim equality and free opportunity for all when not only are some children placed at the finish line, but some are prevented from learning to walk there, even if they wanted to. Education is not only a wonderful development in a person’s life that can allow for the enrichment of one's mind but is also a necessary component of life that provides the skills needed in order to earn a living and survive in this society. If this integral part of life is not provided to citizens equally, can the opportunities in this country really be viewed as accessible to all, and can our society truly be considered unprejudiced? It would seem that as a whole America is attempting to fool itself into believing that it is treating its citizens with equality, and should face these problems rather than sweeping them under the rug.

Perry, I. (n.d.). Reading, Writing, and Rights. In Quality Education As a Constitutional Right

The Effect of Charter Schools on School Segregation

by Rachael Cenicola

New Jersey is forced to face its ever present racial dilemmas after a lawsuit was filed against the state last May. The lawsuit, filed by members of the New Jersey Coalition for Diverse and Inclusive Schools, claims that the New Jersey school system is unconstitutional in terms of segregation.

The lawsuit aims to eliminate two pieces of legislation that currently exist in the state. One is the requirement that students must attend the school district in which they live. The other is the requirement that charter schools in a particular district must give priority to students within that district.

The New Jersey Coalition for Diverse and Inclusive Schools takes specific aim at the racial and economic divide present in New Jersey’s charter schools. “New Jersey’s charter schools exhibit a degree of intense racial and socioeconomic segregation comparable to or even worse than that of the most intensely segregated urban public schools,” the lawsuit states.

When analyzing the racial profiles of New Jersey charter schools versus public schools, the level of segregation is evident. According to a UCLA study on segregation trends in New Jersey schools, roughly 50% of the student body of New Jersey public schools are white. By contrast, the charter school student body is largely comprised of black and latino students, and less than 15% of charter school students are white.

How can there be such a drastic racial difference between the two? The answer can be traced back to the creation of New Jersey’s district lines.

“New Jersey has allowed districts to define their attendance areas,” said Donald Leake, a professor of educational leadership and urban education at The College of New Jersey. “They have drawn attendance areas in such a way that they have created racially identifiable school districts in New Jersey.”

Leake claims that based in its population, New Jersey should have about 200 or 300 school districts, yet the state has over 500 school districts with half of them having less than 500 kids in them. It can be argued that these smaller districts create a homogenous student body with regard to race and socioeconomic status.

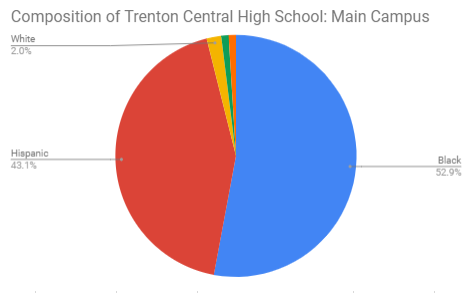

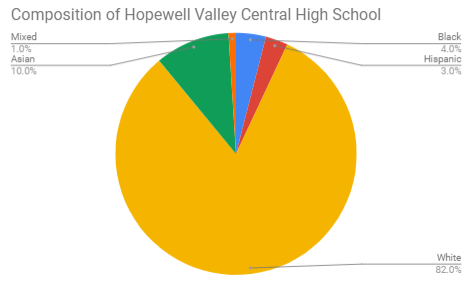

Leake’s observations about New Jersey school districts hold true when comparing the racial and socioeconomic data provided in the lawsuit with charter school statistics provided by the New Jersey Department of Education. Trenton’s district, for example, is 98% nonwhite with at least 89% below the poverty line. Trenton is home to five charter schools, tying with Camden and Plainfield as the city with the fourth most charter schools in the state. Paterson’s 6 charter schools, Jersey City’s 11 charter schools and Newark’s 17 charter schools take the top three spots. All six cities have at least 89% of their district population be nonwhite with at least 62% living in poverty.

Unlike public schools which are both publicly funded and run, charter schools are publicly funded but are run by independent organizations under a charter outlining their performance goals. The schools aim to “assist in promoting comprehensive educational reform by providing a mechanism for the implementation of a variety of educational approaches which may not be available in the traditional public school classroom” as stated by the Charter School Act of 1995. According to the New Jersey Department of Education, 46,000 students attend one of New Jersey’s 88 charter schools.

Leake identifies several problems with the charter school model. “The whole premise of charter schools was that we were supposed to support thoughtful educators with innovative ideas to come out and create a school and relieve them of some of the regulations a public school has. It was building on the premise that a charter school is a better option than a public school, but when you look at the data on charter schools, the performance of charter schools is uneven.” Some charter schools provide quality education while others do not.

Leake goes on to say “Once you started doing creative stuff at the charter schools, you were supposed to come back and share that stuff with the public schools. The coming back never happened, so it created this us against them mentality.” This inadvertent separate but equal education system is what the coalition lawsuit aims to end.

The coalition asserts that allowing students to attend schools outside of their districts is essential in promoting cross racial competence. “School segregation harms all students, including white students, by creating homogeneous learning and social environments. Given the narrowness of their social experiences, students in segregated schools are at greater risk of adopting prejudicial views because rejection of stereotypes, and comfort of interactions across racial lines are predicated on cross racial contact.”

Based on his own experience, Leake said allowing students to attend schools outside of their own district will help alleviate racial segregation but will not integrate students instantly. When asked what can be done to help integrate schools more effectively, Leake said “The single most impactful thing that we can do is to make sure we have highly qualified and effective teachers in classrooms that are culturally sync with students.”

The State of Education in Mercer County: Facing Segregation, Poverty, and Policy

by Katelyn Nieuzytek

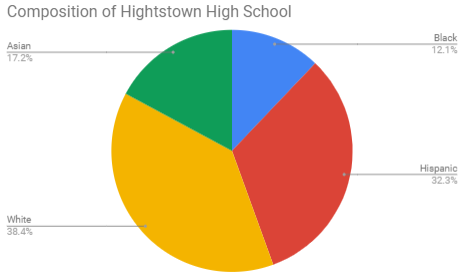

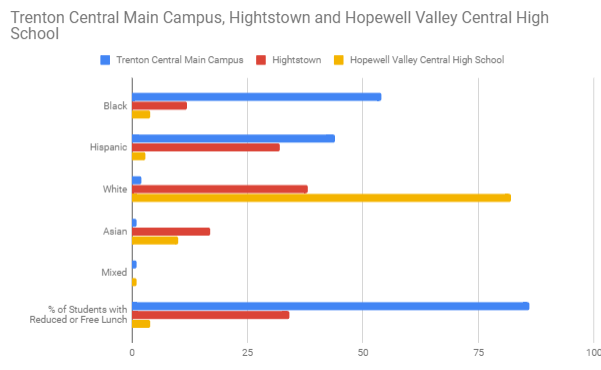

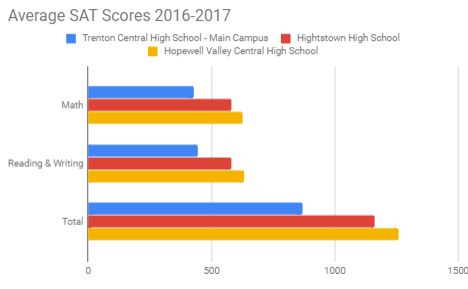

In 1964, the Civil Rights Acts usurped all local and state laws and outlawed segregation in public schools. Nearly fifty-five years later, New Jersey still has one of the most segregated public schools in America. Even within Mercer County, there are high schools which extremely polarized in their composition. This lack of racial and economical diversity only strengthens the divide in education and racial tensions for generations to come.

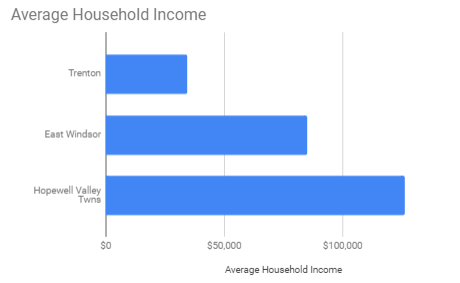

Here are three townships within Mercer County and their average household income according to the US Census Bureau.

Even now, lawmakers are not quite sure how to handle funding in schools. However, Governor Phil Murphy has addressed this issue with a redistribution of aid for the 2018-2019 year, according to the NJ Department of Education. With this new law, some schools will be severely affected with a lost of money, while other high schools will be getting more funding. For Trenton City, the district will receive eleven million more dollars in funding, but the percent difference from 2017-18 to 2018-19 is only 5%. Meanwhile, the Hopewell Valley Regional High School will be receiving a 9.2% increase from last year’s aid, which is $272,989 more. Segregation in New Jersey is less about a legal law, but rather years and years of encouragement for wealthy white communities getting the leg up. With how school funding is structured, poverty-stricken areas will continue to have a lower caliber of education due to funding. While this redistribution plan does benefit Trenton City, there is much more that needs to be done to give children the education needed to pull themselves out of poverty.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.